From BlackWhite magazine - issue 02, green thumbs

An invitation to design for the sheer fun of it has reinvigorated the delight in favouring form over function.

Those who work on the front end of creating built forms are all faced with the same challenge: ensuring that a structure fulfils a functional need but trying to do it in the most aesthetically pleasing way possible. Unfortunately, when the budget begins to dwindle, it's usually the latter part of that goal that suffers. The longer you've been working in the industry, the more you get used to sacrificing the details that would have made your project even more special.

But what if the reverse were true, if it were the function that was stripped away while the form was left intact? It might sound like an impossible theory to apply to a building, but it's something that's been happening for more than four hundred years.

Architectural follies began to appear on great estates in the late 16th century and early 17th century, but they became far more commonplace in the 18th and 19th centuries. During that time, English and French landscape gardening often featured mock Roman temples, symbolising classical virtues while others resembled Asian temples, Egyptian pyramids, ruined medieval castles or abbeys to represent different continents or historical eras. Other times, they represented rustic villages, mills and cottages to symbolise rural virtues. But one thing they all had in common is that they were far more grandiose than typical garden structures, and although costly, they were purely decorative.

The term ‘folly' began as a popular name for any extravagant structure ‘considered to have shown folly in the builder'. Generally speaking, it's a word for small buildings with no practical purpose. It's English connotations of silliness or madness falls into accord with the general meaning of the French word ‘folie'; however, there is historical evidence that an earlier interpretation of the word was ‘delight' – and physical evidence of the same is just a short drive north of Auckland.

When Richard and Christine Didsbury conceived the Brick Bay Folly Project, the couple was inspired by a similar concept regularly undertaken by London's Serpentine Gallery – but with some key differences in criteria. For starters, those creating follies for the Serpentine Gallery have a seemingly unlimited budget and participants are limited to handpicked ‘star architects' who have never done a project in England before.

“We thought it was a fun idea,” says Richard, “but we turned it on its head and decided we wanted to showcase young, undiscovered architects instead. We ideally wanted it to be those who haven't had the chance to ‘prove themselves' yet so that we could give them a chance to do something fun and different, celebrate their creativity and put them on the radar screen.”

2021 will be the seventh year that the competition has taken place, with each bringing about a uniquely beautiful and quirky installation plucked from the minds of the winning architectural student team and coloured with paints and wood stains from Resene. The finished 1:1 scale structures make themselves a temporary home at the Didsbury's 200-acre estate on the coast of Snells Beach, where visitors can experience them in the midst of an idyllic landscape of farmed pasture and native bush.

Richard says that one of the greatest opportunities that the Brick Bay Folly Project offers is a chance for architectural students to learn through the process of doing, as the winners are able to gain applied knowledge they might not have learned otherwise.

“With the programmes that are available now, architectural designers have the ability to render their ideas in three dimensions. But with the folly competition, they have to take that idea and actually build it themselves. The winners may have never hammered a nail before, never mind picked up a skill saw, but they have to be the ones to execute their design.”

“Because of what they can render on the computer, it's common for participants to think they can cut things right down to the millimetre. And in the case of paint, they forget that paint actually has thickness. It may seem small, but if you have a lot of painted surfaces, it can add up to a lot of dimension. But going through the physical process teaches the practicality of understanding the tolerances, the role that skilled contractors play and the value of specifying the right materials.”

That appreciation has been hard earned in a few instances, Richard says. “A few years ago, we had a metal structure where the team applied paint to rebar. They painted into the dusk, and the following morning, they arrived to find that it had sort of dripped off. They'd forgotten that there would be dew overnight, so they had to learn about the specification of paint and allowing proper drying times – and an overall appreciation of what goes into actually doing it.” And they learnt that when it's not done right first time, it has to be done again, with fresh paint applied.

Winning teams also get the benefit of a different type of experience – the opportunity to work with one of the industry's most renowned minds.

“The ability of the teams to interface with some of the greatest architects that we have in New Zealand – Pip Cheshire, and before him, Richard Harris – and have them mentoring them, talking them through their design; what a privilege for them to be able to spend time with these young professionals.

“It's been wonderful watching the people who have been successful with the follies ending up being successful in the industry. Going through the process gives them another layer of maturity. They have another level of awareness and they seem to excel in their firms faster because they have an understanding of taking a project through to fruition. So I think that doing the project accelerates their career, which is fantastic,” says Richard. “Getting them to think about the shape, form, colour, texture, the shadows that you're going to get on surfaces – it really makes their imagination run riot.”

“The satisfaction that we get is the pleasure that the teams get and the learnings that they gain,” adds Christine.

“Participants seem inclined to look to what's happened before, but we don't want them to feel that just because there has been some approach or theme with previous follies that they need to do that as well. We want to see something new,” says Richard.

“We want to celebrate novelty,” adds Christine. “The only constraints are normal health and safety ones, that they need to be robust enough not to collapse when the public interact with them, and that they'll be outside and exposed to the elements.”

As the designers and builders of the first winning folly project, Matt Ritani and Declan Burn didn't have past structures to look to as precedent – they were the ones to set it. Their structure, ‘Belly of the Beast', was opened to the public in March 2015 and pushed the boundaries for what a folly could be.

“Matt and I both saw it as an opportunity to let our creative thinking expand from the university environment of paper/digital representation of ideas to a tangible object existing within the landscape,” says Declan. Our ‘Belly of the Beast' proposal was unrestrained by limitations of scale or buildability through naivety and determination to test our ideas. It was both exciting and frightening at the time to propose a 12 metre tall abstract tower.”

“The Brick Bay Folly Project is very much about platforming new ideas, so it's not so much selfmonumentalising as the original folly makers were. We looked to korowai, kākahu and moana building practices like fale and raupō in terms of forming the beast's shaggy exterior,” says Matt.

“The experience was an extremely steep learning curve, but one I'm grateful for and I think I have much more confidence moving into challenging and uncertain situations having gone through it. I'm amazed at the trust and support that was thrown at two 23 year olds. I had a lot of support from my whānau, boyfriend, friends, family friends and volunteer students who really helped us – and it's honestly as much their project as it is ours. One of the students was pretty much a site foreman for us for most of the summer, and friends would show up and help cut tyres or paint. I also learned heaps from the mentoring and strategic advice from the judging panel.”

His two big takeaways were, “even if you have no idea what you are doing, give it a go and learn along the way, and it really does take a village.”

For Declan, it was the teamwork and communication skills he picked up in the process. “The realisation and appreciation that building a tangible structure is not completed in isolation by solely designers but made with a comprehensive team of dedicated people, that was really important. This experience was pivotal in understanding the whole architectural process from concept design to delivery. Matt and I also quickly learnt the value of open and honest communication with all involved and continued to develop this skillset throughout the project. Discussing ideas to resolve construction details, material orders and site planning with the Brick Bay Folly Project judging panel, building resources, organising student help and ourselves was a steep learning curve.”

It's only been six years, but to Matt the experience feels like a lifetime ago now. He has since become a Project Manager at RCP's Wellington Office focused primarily on civic and institutional projects, and he believes that participating in the Brick Bay Folly Project programme has definitely had a positive impact on his career.

“The fact that we had not even finished university yet and had our first built project come out as pretty much what we proposed was great. I think perhaps a side effect of this, which I really believe will serve me better as a designer in the long run, is that it has made me uncompromising conceptually. As a maker, I try to be direct, clear and specific in my work and I think this approach comes directly out of working on the folly. Having the idea of a project in which every detail is considered and is in service of a very specific conceptual position is really important to me and ‘the beast' was a good first road test of this at a large scale.”

“For instance, the bark in the floor of the space was a red bark, but it wasn't quite the exact red we wanted, so we put it in a concrete mixer with buckets and buckets of Resene paint – like, we basically ran the Mount Eden Resene ColorShop out of red base. And it would probably have been fine without it, but it added a little zing to it, and things like that add up and are worth doing.”

“The skills I learnt during the Brick Bay Folly Project have become the foundation of my professional tool kit,” says Declan. “They're fundamentals that I use every day of my practising career. Building the original proposal also gave both Matt and I the confidence to not compromise on our design ideas or ambition for crafting works both conceptually and at scale when we are out of our comfort zones.

“We have so much appreciation for Richard and Christine Didsbury and the Brick Bay team; Resene for supplying paints, brushes, drop cloths and other supplies; Richard Harris for believing in Matt and I, Unitec for the facilities and the fantastic students – who gave us so many hours of their time – who all helped us to realise this project. I would encourage anyone to enter the next Brick Bay Folly Project as the experience, skillset, and friends made will last with you forever,” says Declan.

“It was an amazing experience, and taking a summer off to build a folly is a privilege that not everyone has access to, and I feel very fortunate to have been able to do that,” adds Matt.

Last year, Brick Bay's programming expanded to include a new competition for landscape architects who were tired of sitting on the sidelines.

“We started the Nohonga Design Challenge last year because we were quite restricted with the follies, as our guidelines were the entrants had to be qualified architects finishing up at architecture school,” says Richard. “But, of course, because we were excluding landscape architects, we dreamed up something more around the public realm that utilises their skills – which we don't let architects into!”

Named for the Te Reo Māori word for ‘seat', the Nohonga Design Challenge is a collaboration between Brick Bay and Tuia Pito Ora New Zealand Institute of Landscape Architects' Auckland Branch. It not only challenges students but all levels of graduated landscape architects to design and construct creative nohonga.

Five winning bench designs were selected, and those teams were able to make their mark on Auckland's urban landscape through a variety of shapes and materials finished with Resene paints and wood stains. The completed designs were first showcased in Britomart's Takutai Square before making their way to Brick Bay.

In addition to the folly and nohonga projects, Brick Bay is also home to an exhibition of contemporary sculpture by celebrated artists. The chance to see these dynamic large-scale creations set in a stunning natural environment draws visitors from far and wide.

Richard and Christine are especially proud that they are able to offer up space to display the follies and nohonga, if only temporarily. “It's important to share them with the public,” says Richard. “Wouldn't it be great if we could stimulate potential future clients to push boundaries and ideas because of it, that they would come to their architects after seeing these ideas and want to find ways to incorporate them?

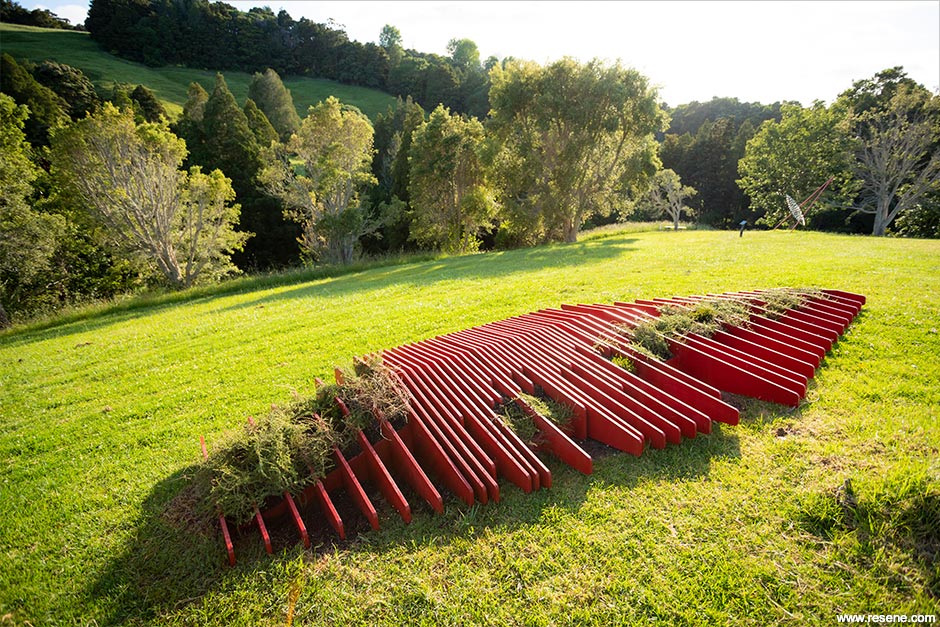

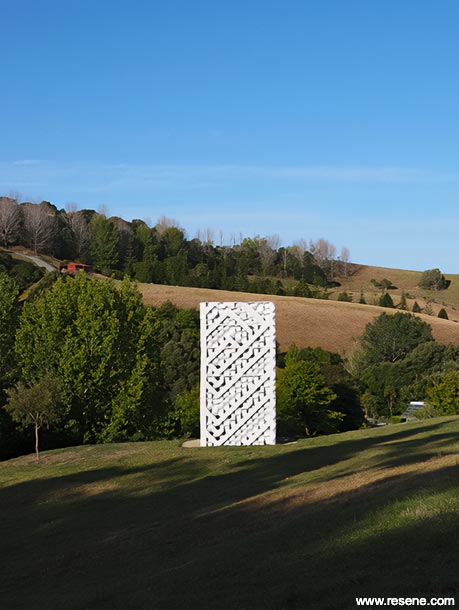

‘Genealogy of the Pacific' (2020/21)

“People also enjoy the fact that they can get enveloped with something creative. The follies are often made with the most basic of materials, but it's the way that they've been shaped and put together that makes them interesting.”

“We like to play the fly on the wall and see the visitor's sense of joy when they approach these structures, both the folly and the nohonga,” says Christine. “The fact that they can physically interact, that they can touch them and sit on them, it gives them the opportunity to do something that they can't do with other sculptures on the property. Seeing children touch them and play on them adds another layer of joy to the experience.”

Christine recalls the amusement of watching guests interact with ‘Daughter of the Swamp', the 2016 winner. The design was inspired by an eel pot or hīnaki form. “You'd watch children run straight through it and then adults have to bend down to get through it. It was so much fun to witness.”

“The current folly, ‘Genealogy of the Pacific', is especially deceptive,” says Richard. “It appears to be simple, but it's got incredible texture and it has good resonances to it. So perhaps there will be some future clients who are encouraged to brief their architects on applying some of those ideas.

“And people will often look at them and say, ‘well, I could do that.' Wouldn't it be wonderful if they actually did? If they went home and took up some timber and tools and built something fun like that themselves?”

“When we have to pull them apart at the end, we're sad to do it – they've all been exciting and had worth – but we're also excited to do it because we know that something new will be coming in its place,” says Christine.

“We also don't see the role of Brick Bay as hosting them in perpetuity, as the spaces we put them in get refreshed every year. But if they're made with permanent materials, we'll try to find a space within the public realm where we can put them so that people can continue to enjoy them,” adds Richard.

While what is and isn't a folly is ultimately subjective, Richard believes that a folly has to be more architectural while other creations fall more into the sculptural realm. “But we don't give anyone a definition,” he says. “You create your own definition.”

“Some of the submissions we get for the Brick Bay Folly Project verge on the sculptural, but we try and encourage designs that you can walk inside of so that they envelope you. The competition challenges the norms of built form and lines and gives freedom to create texture, form and light. But it also takes a lot of typical constraints away. They're just meant to be enjoyed for what they are in the time that they're around.”

By referencing the earlier definition of ‘delight', whether or not an outdoor structure that invites interaction is truly a folly is inconsequential. What's far more important is the sense of joy it brings – and that's something we can always invite more of into our lives.

For more on the Brick Bay Folly Project, visit www.brickbaysculpture.co.nz/folly-overview.

Whimsical wonders

These brilliant big things may not officially count as true follies, but they certainly bring delight.

Every Queenslander knows The Big Pineapple, and it has been a firm fixture in childhood memories since it was built in 1971. Made of fibreglass, it stands 16 metres tall at the entrance to the Sunshine Plantation, a tourist theme park near Nambour, Australia. The Big Pineapple is now heritage listed and cherished by Queensland Tourism and the Sunshine Coast community along with many visitors who visit the area on holiday. Vicky Pattison from Art of Crazy, undertook its most recent repaint. It was topcoated with Resene Hi-Glo gloss finish for maximum impact in a palette of Resene Turbo, Resene Surfs Up, Resene Havoc, Resene Crusoe, Resene Black and Resene White.

The pineapple of our eye

Not quite world famous

The iconic soda Lemon & Paeroa (L&P) can only be found in New Zealand and in specialty stores abroad. The beverage was traditionally made by mixing carbonated mineral water from Paeroa's natural springs with lemon juice. Unfortunately, at seven metres tall, its enlarged representation isn't the largest soda in the world – so it's still only world famous in New Zealand. But now that it's had a refresh in Resene Lumbersider tinted to Resene Brown Pod, Resene Bright Red and custom made Resene L&P Yellow, all topcoated in Resene Uracryl GraffitiShield, it will continue to look the part for ages.

The world's largest carrot rests in the town of Ohakune, an area famed for its farms and carrot production, and was originally built for a television commercial for a major bank before being donated to the town. At seven and a half metres tall, it's also the biggest vegetable in New Zealand and gets its carrot-like colour thanks to Resene Ecstasy. It's stood in the same spot at the eastern entrance to the town since 1984, but now it's kept company by the adjacent Ohakune Carrot Adventure Park. In 2011, the carrot was turned into the country's biggest sports fan with a temporary repaint in Resene CoolColour Black paint and Resene Sea Fog, as part of the ‘Paint it Black' campaign leading up to the Rugby World Cup. It has since returned to its orange origins.

This is a magazine created for the industry, by the industry and with the industry – and a publication like this is only possible because of New Zealand and Australia's remarkably talented and loyal Resene specifiers and users.

If you have a project finished in Resene paints, wood stains or coatings, whether it is strikingly colourful, beautifully tonal, a haven of natural stained and clear finishes, wonderfully unique or anything in between, we'd love to see it and have the opportunity to showcase it. Submit your projects online or email editor@blackwhitemag.com. You're welcome to share as many projects as you would like, whenever it suits. We look forward to seeing what you've been busy creating.

Earn CPD reading this magazine – If you're a specifier, earn ADNZ or NZRAB CPD points by reading BlackWhite magazine. Once you've read an issue request your CPD points via the CPD portal for ADNZ (for NZ architectural designers) or NZRAB (for NZ architects).